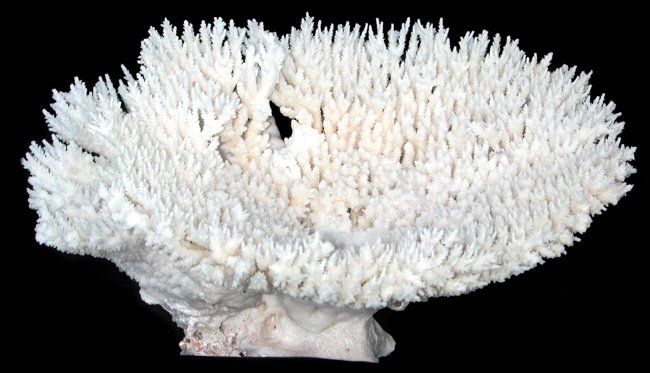

Table Coral Cluster measuring 7 to 10 inches (fly not included) ******

One Table Coral Cluster measuring 7 to 10 inches

Orders usually process within 2 to 5 business days.

Email us at ja1@mindspring.com Make Your Selections and Shipping Preference. We Will Email You the amount of the Shipping Cost. When you receive the shipping cost go back into Shells of Aquarius and click into Purchase Shipping Label. There you will find UPS or USPS. Click into the option you decided on and make your payment. Your order will ship when shipping payment is received.

This is a genus of small polyp stony coral in the phylum Cnidaria. Other species within the Acropora genus are known as elkhorn coral, and staghorn coral. This genus consists of over 149 species. Acropora species are some of the major reef corals responsible for building the immense calcium carbonate substructure that supports the thin living skin of a reef.

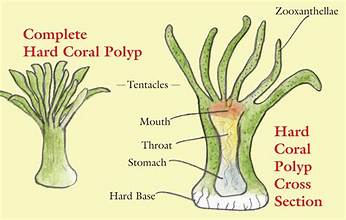

stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mouth is fringed with tentacles. Although some species are solitary, most are colonial. The founding polyp settles and starts to secrete calcium carbonate to protect its soft body. Solitary corals can be as much as 10 inches across but in colonial species the polyps are usually only a few fractions of an inch in diameter. These polyps reproduce asexually by budding, but remain attached to each other, forming a multi-polyp colony of clones with a common skeleton, which may be up to several feet in diameter or height according to species.

Depending on the species and location, Acropora species may grow as plates or slender or broad branches. Like other corals, Acropora corals are colonies of individual polyps, which are less than an inch across and share tissue and a nerve net. The polyps can withdraw back into the coral in response to movement or disturbance by potential predators, but when undisturbed, they protrude slightly. The polyps typically extend further at night to help capture plankton and organic matter from the water.

More than 100 species are distributed in the Indo-Pacific and 3 have been found in the Caribbean. The true number of species is unknown: the validity of many of these species is questioned, as some have been shown to represent hybrids, for example Acropora prolifera; and some species have been shown to represent cryptic species complexes.

Symbiodinium, symbiotic algae, live in the corals' cells and produce energy for the animals through photosynthesis. Environmental destruction has led to a dwindling of populations of Acropora, along with other coral species. Acropora is especially susceptible to bleaching when stressed. Bleaching is due to the loss of the coral's zooxanthellae, which are a golden-brown color. Bleached corals are stark white and may die if new Symbiodinium cells cannot be assimilated. Common causes of bleaching and coral death include pollution, abnormally warm water temperatures, increased ocean acidification, sedimentation, and eutrophication.

Coral bleaching is the process when corals become white due to loss of symbiotic algae and photosynthetic pigments. This loss of pigment can be caused by various stressors, such as changes in temperature, light, or nutrients. Bleaching occurs when coral polyps expel the zooxanthellae (dinoflagellates that are commonly referred to as algae) that live inside their tissue, causing the coral to turn white. The zooxanthellae are photosynthetic, and as the water temperature rises, they begin to produce reactive oxygen species. This is toxic to the coral, so the coral expels the zooxanthellae. Since the zooxanthellae produce the majority of coral coloration, the coral tissue becomes transparent, revealing the coral skeleton made of calcium carbonate. Most bleached corals appear bright white, but some are blue, yellow, or pink due to pigment proteins in the coral.

he leading cause of coral bleaching is rising ocean temperatures due to climate change caused by anthropogenic activities. A temperature about 2 °F above average can cause bleaching. The ocean takes in a large portion of the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions produced by human activity. Although this uptake helps regulate global warming, it is also changing the chemistry of the ocean in ways never seen before. Ocean acidification (OA) is the decline in seawater pH caused by absorption of anthropogenic carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This decrease in seawater pH has a significant effect on marine ecosystems.

According to the United Nations Environment Program, between 2014 and 2016, the longest recorded global bleaching events killed coral on an unprecedented scale. In 2016, bleaching of coral on the Great Barrier Reef killed 29 to 50 percent of the reef's coral. In 2017, the bleaching extended into the central region of the reef. The average interval between bleaching events has halved between 1980 and 2016. The world's most bleaching-tolerant corals can be found in the southern Persian/Arabian Gulf. Some of these corals bleach only when water temperatures exceed 95 °F.

Most Acropora species are brown or green, but a few are brightly colored, and those rare corals are prized by aquarists. Captive propagation of Acropora is widespread in the reef-keeping community. Given the right conditions, many Acropora species grow quickly, and individual colonies can exceed a foot across in the wild. In a well-maintained reef aquarium, finger-sized fragments can grow into medicine ball-sized colonies in one to two years. Captive specimens are steadily undergoing changes due to selection which enable them to thrive in the home aquarium. In some cases, fragments of captive specimens are used to repopulate barren reefs in the wild.

Bleached corals continue to live, but they are more vulnerable to disease and starvation. Zooxanthellae provide up to 90 percent of the coral's energy, so corals are deprived of nutrients when zooxanthellae are expelled. Some corals recover if conditions return to normal, and some corals can feed themselves. However, the majority of coral without zooxanthellae starve.

Scientific classification

Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Cnidaria

Class: Hexacorallia

Order: Scleractinia

Family: Acroporidae

Genus: Acropora

Oken, 1815

(REF: Wallace, C. C; Rosen, B. R (2006-04-22). "Diverse staghorn corals (Acropora) in high-latitude Eocene assemblages: implications for the evolution of modern diversity patterns of reef corals". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 )(REF: WoRMS (2010). "Acropora Oken, 1815". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2012-02-10.)(REF: "Acropora". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.)(REF: Acropora at Encyclopedia of Life Archived 2011-08-12 at the Wayback Machine)(REF: Vollmer, S.; Palumbi, S. (2002). "Hybridization and the Evolution of Reef Coral Diversity". Science. 296)(REF: Ladner, Jason T.; Palumbi, Stephen R. (2012). "Extensive sympatry, cryptic diversity and introgression throughout the geographic distribution of two coral species complexes". Molecular Ecology. 21 )(REF: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Adding 20 Coral Species to the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife" (PDF). Federal Register. 79)(REF: "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Acropora Oken, 1815". www.marinespecies.org. )(REF:NOAA Coral Reef Information System (CoRIS))